NOTE: Here is the text from a brief conference I was asked to give in my children’s school for a Lenten Retreat focusing on Who is my neighbor? Cultivating a heart of mercy.

One of the goals of our school’s Mission Statement is “A social awareness that impels to action.” Or as I like to translate it – a faith-life that impels to action.

Impel. This is exactly what happened while Mark and I lived in West Philadelphia. As UPenn graduates, we saw privilege, surrounded at all sides by poverty, but once we walked among the people who lived that poverty, we couldn’t turn our backs on them. We were impelled to act.

As newly weds and new college grads, Mark and I owned the only home we could afford, a beautiful three-story house in a “condemned neighborhood” as one African-American woman said to the realtor when we were trying to sell it, before our move to California.

During the eighties and nineties, drugs poured into urban cities throughout the United States. Nobody really knew it back then, but the United States government was arming the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, and profits somehow got in the hands of powerful drug cartels in Colombia. The result was the crack epidemic and we lived in a house in West Philadelphia during its height.

On the news, we saw our neighborhood being portrayed as a place of death, crime, violence – perpetrated predominantly by African-Americans. The war on drugs had started and a whole generation of young black men were criminalized and jailed.

Yes, there were drug dealers on every street corner and we feared for our lives because of the random violence, but we saw more than that. As West Philly community members who lived in the ‘hood’ we saw beautiful people who valued real friendships. We saw a community trying to hold itself together despite all odds and loving one another authentically.

I often chatted on the front porches with grandmothers who were waiting for their sons to get out of jail and others who watched their children succumb to crack addiction; I sat on rowhome steps early in the morning with a prostitute who spoke with a German accent, after she had just finished her evening shift.

I would also talk with schizophrenics who lived in a nearby group home, for as long as I could follow the string of their confused thoughts. And I spent many evenings trying to convince thirteen-year-old girls from the projects that love wasn’t about handing our bodies over to any boy with empty words.

In this invisible war zone in plain site, people tried to help one another any way we could. I was once pushed out of three feet of snow by a man with scars that ran down his cheek and who once led the Junior Black Mafia. A drug dealer protected Mark from teens who weren’t part of the neighborhood, and who seemed ready to shoot him after he tried to stop them from tagging a wall.

And when the main water pipe from the third floor in our house broke, ruining our first floor walls and ceilings while Mark was away on a trip abroad, it was a young man who had just been released from jail, who spent three days replacing the plaster. He wouldn’t take any more than $50 from me.

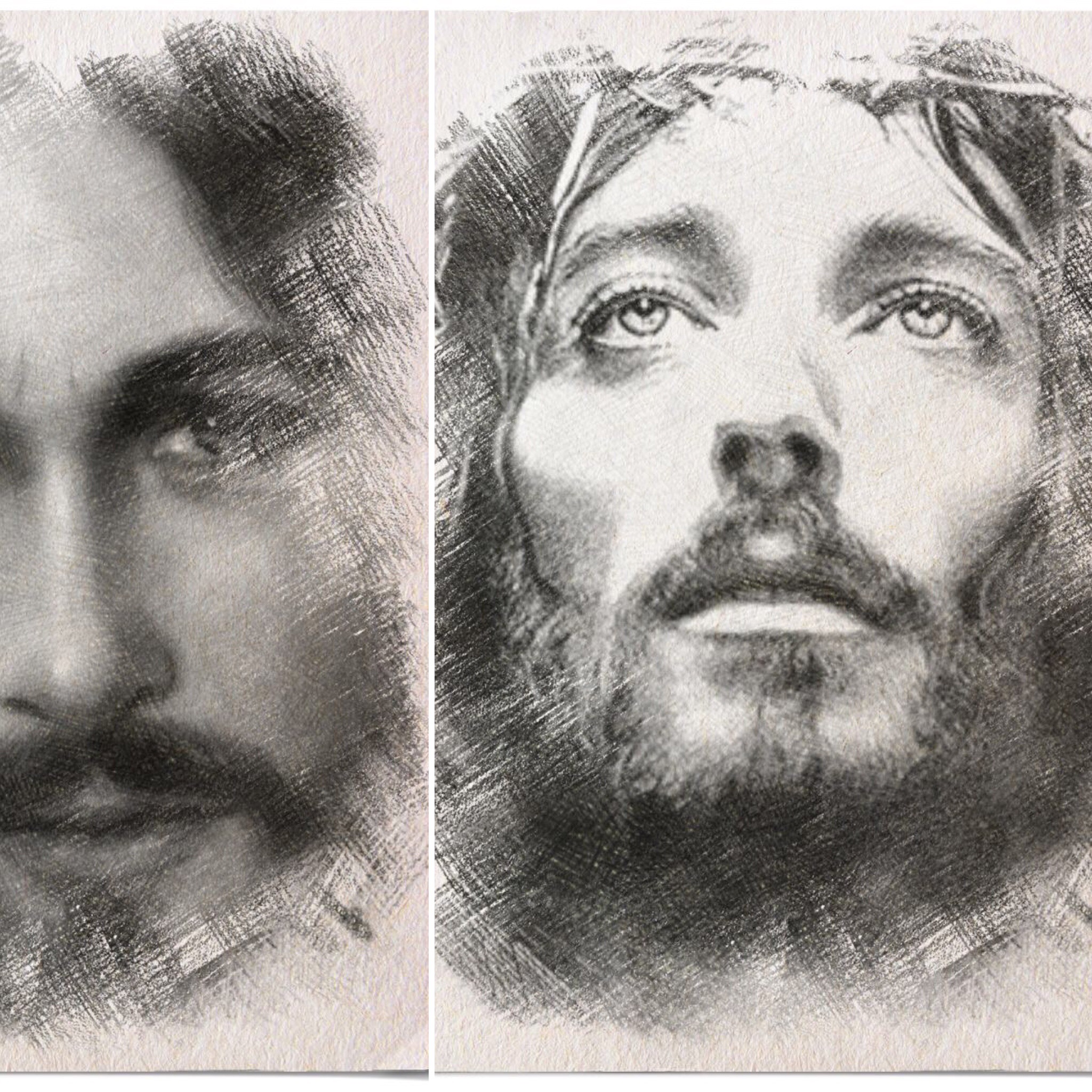

A personal encounter with the suffering of Christ in the suffering of people changes a person, and once we came face to face with this wholly different narrative, we couldn’t turn our backs.

We lived in West Philadelphia for fifteen years and in that time until now, I’ve willfully chosen to work with urban communities in my teaching. It’s a job that has terrible pay, earns me absolutely no social capital, and requires many weekend hours of grading.

Because of my teaching schedule, I can’t be involved very much in the school community, where meetings often happen early in the morning, when I am teaching. But I know that with my parenting support at home, that my now four children will be fine.

So yes, there have been many sacrifices. Yet I do it because I want to give young people who have so much stacked against them a chance of pulling their lives together through an education that can lead to a financially stable career.

As parents, we give our children every single kind of advantage we are able to give . We give them financial support, emotional support, tutoring instructors, summer camps and international travel.

At-risk students who live in poor communities are just as capable and deserving of those opportunities as our own children. The only difference is that they do not have the kinds of support we are able to provide.

A poem I wrote a few years ago captures why I am impelled to work with marginalized communities:

THEY ARE CHRIST

Crucified by human weakness, yet they still appear through the classroom doorway each day.

Young people who care for dying family members,

Squeezing studies between a forty-hour work week

And visits to the hospital,

Barely adults themselves, they are thrust forcefully into adulthood

And overnight, after a parent has suddenly died or disappeared,

Must become from brother to father; daughter to mother.

The virility of youth, stolen,

Without warning

By brain disease, cancer, blindness.

A stray bullet. Intentional gunfire. Knife wounds.

Hopes shattered,

By an American Dream that must be delayed, seemingly into eternity,

For families who trekked hundreds of miles on foot,

To a land that held twisted, broken promises.

The poor, the misunderstood, the invisible.

The scapegoats of the failures of society.

Everyday,

The eyes of these beautiful souls

Look up at me from their seats,

And I am deeply humbled.

They… they are Christ crucified.

Blessed are the poor, for theirs is the kingdom of God.